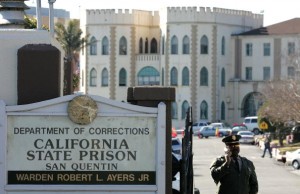

It was 8:30 a.m. on an August morning and I was listening to a trustee at the chapel inside of

San Quentin State Prison tell me and other public health professionals about our assignments for the 11th Annual San Quentin Health Fair.

“Only talk to inmates if you have a question about setup for the health fair,” the trustee said. “Talk to an officer only if you need to go anywhere in the prison, because you have to be escorted.”

“Don’t give inmates any personal information,” he warned. “Be friendly but professional.”

My work as an Advance Health and Hospice Systems Coordinator for Alameda County includes outreach to diverse populations. I was recently inspired by Michele Alexander’s powerful book,

New Jim Crow, which talks about the legislation and laws—and financial incentives—resulting in the incarceration of a staggering number of African American and Latino men. So when I was invited by the Alameda County Public Health Department to participate in the Health Fair at San Quentin, I said yes.

I asked a notary to join me to notarize the completed advance directives, and we were both overwhelmed by the sheer number of inmates waiting for us. More than 1,000 men were waiting to be seen for screenings and to get information. We were not sure what to say when the men began approaching our table.

The first inmate I spoke with was an elderly man. He said he was healthy and did not need an advance directive.

“Everyone needs to make some decisions,” I said. “If you don’t make decisions about your care the prison will make them for you.”

“Why didn’t you say that in the first place?” he said. I struck a chord.

I soon realized inmates are keenly interested in maintaining as much control over their bodies as possible.

Throughout the day I had quality conversations about life, death, and organ donation. Serious discussions occurred and decisions were made as I helped men complete the forms. Over the three and a half hours we worked at the health fair we notarized 20 advance directives.

My final reflection about the San Quentin Health Fair is from a question on the

user-friendly California Advance Healthcare Directive. “What should your doctor know about how you want your body to be treated after you die?” it asks.

Universally, each inmate responded, “I want to be treated respectfully.”

Marilyn Ababio, HCSA, is an advance health systems coordinator for the

Alameda County Health Services Agency, and serves on the CCCC advance care planning coalition.